This was one of the first stories I ever had published, about 20 years ago now. It appeared in an anthology by Tindal Street Press, called The Sea in Birmingham. Unfortunately (from my point of view at least) the editor saw fit to take out all the good bits, including all the stuff about Poppet, because she thought it was silly. As far as I was concerned, this killed the story. The editor was a pretty well known literary figure, and I was too intimidated and inexperienced to battle for my vision of the story, but it taught me a useful lesson about how to deal with editors and publishers and when to stand my ground. Anyway, this is the original version of the story, with all the good bits left in!

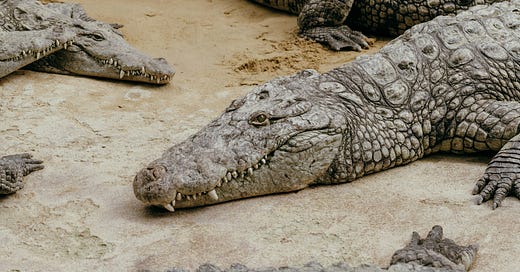

THE GLITTERING CROCODILES

The man was dead. Bobbing at the edge of the canal, skin greenish-white and just beginning to bloat up. No one spoke as they heaved him out of the water. Even the birds stopped singing for a moment, when the officers spread his sodden body over the towpath. The silence felt like a halo of pressure around my head, squeezing my brain, just enough to give me a headache. But then the radio crackled and someone choked out a morbid laugh, and it was just as if someone had turned up the volume of the world again.

The drowned man's name was Greg Odell. When I heard it, I thought about the glittering crocodiles that live on the banks of the Nile. How their scales are jewelled with diamond drops of water. How the white sun refracts into the entire spectrum of colour across their backs. How they glint, like teeth, in the grass. The picture came from memory – the memory of a photograph in a children's encyclopaedia, which I had once held open on my lap for hours, when it had been too wet to go outside. All afternoon, I had gazed alternately at the picture and then through the window at the rain. So in my mind, my memory, the glittering crocodiles are resting within the frame of a window. The Nile ran across one edge, calm as satin, and the grass rose in vivid points. The crocodiles lounged, heads turned to the left, eyes blackened by the sun. Outside the frame it was perpetually raining, a fine grey drizzle that pulled the skies down low over the houses. My mouth filled with the taste of sweet rice pudding, sugary milk coating my tongue and teeth. The tink of the spoon in the bowl.

It’s been a long time since I’ve tasted rice pudding. My mother had had a sweet tooth; she often cooked those kinds of things. It’s better not to remember. Nothing good comes from thinking about the past. That day, at the canal side, I knew that this was special evidence and I berated myself that I could not think what it all reminded me of.

You don't remember because you're a stinky, lazy boy, said Poppet. I pushed her head down into the depths of my pocket. Stupid little doll.

Greg Odell had been a lawyer before he wound up in the canal. He had a wife and a couple of kids, lived in one of those big Victorian places in Edgbaston. Probably had a lot of enemies, I shouldn’t wonder. Probably everyone hated him, smug bastard, with his posh house and his pretty wife and spoiled-rotten kids. And no one likes lawyers, do they? Especially not coppers. But it didn’t look suspicious, not on the surface anyway. Nicky Newlove, my partner, thought it was a straightforward accident, said there was no evidence of foul play. We asked around, but no one had anything to tell us. It was all shrugged shoulders and sorry expressions.

"No one knows anything," Newlove said. "Because there’s fuck all to know." She had her feet up on her desk, so I could see the soles of her shoes. Mud and leaves wedged into the grooves, from where we’d been walking up and down the side of the canal. I clean my shoes every day, but you can’t expect other people to be as fastidious.

“I don’t believe in accidents, Newlove. You know that.” Something didn't sit right with me about the whole thing, but Newlove was immune to hunches and intuitions. She was a straight down the line, no nonsense, by the book copper. It takes all sorts to make a world, as I often have cause to remind myself. "Let’s go for a smoke," I said. That was one thing Newlove and I had in common: we were both serious smokers. Me, I started when I was nine years old. I'd been bored. My mother smoked, and she accidentally left her cigarettes and lighter on the dresser in my room.

She wanted you to start smoking.

Of course she didn't. She’d just forgotten them. I remember picking them up. Benson and Hedges. The packet was gold and shiny, tight with cigarettes. You could smell them through the cardboard. When I lit my first cigarette, there was a dry crackle and smoke filled my lungs. I knew how to do it – I had been watching her all those years, after all. I didn't even cough.

You coughed like a dog. You threw up, out of the window. Crows pecked at your vomit.

I was a natural. Took to it like a duck to water. Thirty-five years later, I'm on two packs a day. Never even tried to stop.

Newlove was a different story. Every other week, it was something else. Hypnosis, patches, glass of water every time she felt a craving (which was a disaster – we kept having to stop interviews so she could go to the loo.) She tried everything. The problem was that she loved it too much. And I had to admit, it suited her. The O of her mouth, when she blew the smoke into the rain, made me wonder what it would be like to kiss her. Perhaps to put my mouth over hers and suck the smoke from her lungs into mine. But you don't go there with your partner, not unless you're looking for trouble. Besides, I wasn’t Newlove's type. She had some smooth-faced girlfriend in Operations; she was the one who was always telling her to quit smoking.

"I don't get it," I said. "So this guy's walking home from work, in his business suit and everything, and he just so happens to fall into the canal and drown? Just like that?"

"Why not? He'd been drinking, him and his colleagues. He was drunk, lost his footing."

I guessed it was plausible, but it didn't ring true. I waited a moment, to try to hear Poppet's thoughts, but she was silent. So I said, "Have you ever made rice pudding, Newlove?"

"I've bought it, from a shop."

"No, then."

Put the milk, sugar, rice and butter in the bottom of a glass bowl. Add full cream milk. Tap your cigarette ash onto the surface. Stir everything together.

Nutmeg. Cinnamon. Not cigarette ash.

Whatever.

"It's easy to make," Newlove said. "I mean, I've never done it, but all you need is…"

"All right, Delia Smith. I don’t need a recipe."

Newlove took another drag of her cigarette and blew the smoke towards me. Her eyes narrowed with pleasure. "Fuck. I really must stop smoking. Have we talked to his boss yet?"

"No. Get statements from the colleagues, too. Find out who saw him leave the pub."

"Forensics said it all looked kosher. No sign of a struggle. I don't think there's anything suspicious here."

"Come on, Newlove! Of course it’s suspicious. It’s a bit too much of a coincidence, don’t you think?"

“Sorry? What are you talking about now?”

I ignored her tone, and said, “There are more miles of canal in Birmingham than there are in Venice. Did you know that?” Because she hadn’t grown up here, she might not be aware of some of the common geographical features.

“You’ve mentioned it before, yes. I fail to see how it’s relevant at the moment.”

“Well, perhaps it isn’t. Perhaps not. But it doesn’t hurt to be in possession of all the facts. And out of all those miles and miles of canal, Odell just happens to wash up on our patch? Coincidence, you say?”

She gave me a strange look, then. Or rather, she looked at me as though I were strange. I really would have liked to explain myself better, but I didn’t know how. I feel the same way just now, if I’m honest. You’d think it would be easier to put it all in writing, that maybe it would make sense of things, stack it up in the order it happened. It doesn’t seem to be helping much just yet.

It had something to do with the glittering crocodiles, of course, but beyond that I couldn't say what it was about Odell's death that particularly bothered me. He was drunk, he slipped. It was a bad bit of the canal, maybe. His wife said that Odell often walked that way home, which was plausible. It was derelict and uninviting, but a short cut. Some said that the canals were full of dead bodies, dogs, snakes – but clearly that didn't bother Odell. His colleagues described him as sensible. Everything about Odell was unremarkable, even boring, barely worthy of notice. Yet he stood out to me, startlingly vivid, and I knew that he was a part of my story. Perhaps even the key.

You know them when you see them.

I walked home by the canal. There was the usual haul, nothing special. I found a couple of shoes, one men's size ten brogue, the other a size five training shoe with a hole in the bottom. A child's blue hooded cardigan, hanging from a twig. A thin rain jacket, twisted and stuffed into the hole in a tree trunk. A pair of brown corduroy trousers, lying on the towpath like a pair of drunken legs. I shoved them all into my rucksack, to be taken away for further investigation. It was a mystery to me how these things came to be there. A cardigan, I could understand. You took it off because you were too hot, and it slipped from your hand or from around your waist. But trousers? How do you lose a pair of trousers? How do you lose a shoe? Surely you would notice if you were walking along and suddenly you only had one shoe. I had found other things at the canal. Other, special things. Suit jackets, ties, a black high-heeled stiletto.

High heels with sharp points. Useful punishers for bad children.

Shut up, Poppet.

When I got home, I went straight down the gully into the back. All the stuff from the canal went into the Evidence Shed at the bottom of the garden. I tried to keep it organised, but the only real system was that the older the evidence, the deeper in the pile it was buried. I slung this latest stuff on the top. The special things, the high-heeled shoe and other important things, were in bags on the shelf. I thought about getting all the special evidence together and going through it again, but really I just wanted a couple of beers. Besides, it stank to high heaven in the Evidence Shed. Stank of canals.

In the house it was much better. Smelled of Summer Breeze air freshener I'd plugged into all the wall sockets. That Summer Breeze fragrance is better than nature. It hit me in the back of the throat when I walked through the door. Everyone likes a fresh-smelling house, don't they? That made me think about Greg Odell. He had breath mints in his trouser pocket when they pulled him out of the canal. Those really strong ones, blow your mouth off. What did he want those for?

Doesn't matter how much you wash, you can't wash off a bad smell like yours. Stinking child.

I wrapped my fist around Poppet's head and squeezed, to shut her up. Now Greg Odell, he’d been drinking all afternoon, but that was no secret. His wife told us he'd been celebrating with his work friends, some big case they’d won or something. So it wasn't his boozing he was trying to cover up. Something else. And suddenly, I knew what it must be.

"So, he's a secret smoker. So what?" Newlove tapped her fingers against the desk. "It's hardly a crime. Hardly a motive for murder, either."

"Murder? Who said anything about murder?" I leaned forward, over the desk.

"I thought… oh never mind," said Newlove. "Can we just close the case, please? Nothing but nothing is going on here."

"You are so wrong, Newlove, that I hardly how to begin telling you just how wrong you are."

"Fine by me." She stood up, patted her pockets for her cigarettes. "I'll just be wrong and ignorant to boot, then, shall I? Excuse me."

"Damn it." I followed her outside, noting that great stride she had. No one messed with Newlove. Except maybe me, on a bad day. She kept walking all the way to the car park, then stopped and leaned against the bonnet of her Ford.

"I'm never going to hear the end of this, am I?" She lit a cigarette and blew the smoke towards me. She really was a fine looking woman, even when she was looking at me like she wanted to stab me in the face.

"The point is, why was he lying? And who was he lying to?"

"But why does it matter? He fell in the fucking canal! Haven't we got any real work to do? By which I mean, actual crimes."

She's got a point, whispered Poppet.

"Okay! Fine. Close the file." I snatched the cigarette from between Newlove's fingers and took a drag. She glared at me. I grinned.

Why don't you tell her about the crocodiles?

"Oh shut up," I said, out loud.

Newlove shook her head. "I worry about you, mate. I honestly do."

My mother's room was more or less exactly as she'd left it. Not that she had left it. She had died, though, and that's what I mean by that. Sometimes, after I'd had a few drinks, I'd go and stand in there and look through her stuff. I did that now, looking for anything that would lead me to Greg Odell. The file might be closed, but I wasn't convinced. Something had gone down that day, the day he died, and I couldn't let it go.

I found the children's encyclopaedia, all seven volumes of it. The red leatherette binding had lasted well, but the gold lettering had eroded, so I couldn't tell which volume contained which alphabetical references. I had to open the books to the flyleaf to see the titles. I started by looking under C for crocodiles. There was a picture of a crocodile, but not the picture I remembered. There was a guy standing over the crocodile, holding its jaws apart. Next to the picture was a drawing of the crocodile's mouth full of teeth. I read through the entry. Nothing. But at the side of the page was a little box of text entitled 'Crocodile Tears'. Oh yes, I thought to myself. They get your sympathy then bite your head off.

I picked up all seven volumes of the encyclopaedia to take downstairs with me. Before I left the room, I gave it a good spray with air freshener.

Stinky boy.

I pulled Poppet from my pocket and sprayed Summer Breeze into her face. A good long blast of it. She never says anything when she's out of my pocket, just goes limp and doll-like. You can feel the cotton wool under the fabric, all springy. When I stuffed her back into my pocket, she yelled at me –

You smell of poo!

"You smell like a summer breeze," I replied.

You're going to get into trouble!

I pushed my fingers into Poppet's head, pushing the fabric down into the stuffing. Sometimes I think I should just throw her on the fire. But I'm scared that she would come back worse than she already is.

The next day was a Saturday, so officially I was off duty. But I like to think that a good copper is never really off duty. I took the bus into town, and walked the canal towpath to Edgbaston, coming out on Gillot Road. That had been Greg Odell's usual route home. I looked for a place where he might have fallen. Even though the towpath is pretty rough here and there, there’s a clearly defined kerb that runs all the way along his route. You'd have to be fairly drunk to fall over that. Mind you, his work colleagues said he'd been downing shots and pints like nobody's business. Of course, no one tried to stop him, take him home or anything like that. Lawyers, eh? Scumbags.

His house was one of those mansion-type of places, three floors, the columns either side of the front porch, three cars in the driveway – all beemers. If I'm honest, it made me feel a bit self-conscious about my Saturday clothes. I had a shirt and tie on, but I was wearing jeans and trainers on my bottom half. I'd given myself a good dose of Summer Breeze before I left the house, so at least I smelled nice. Mrs Odell opened the door after the third ring. She frowned at me, looking me up and down as if she couldn’t possibly imagine what I was doing ringing her doorbell. Her face was thin and drawn, no make-up, and maybe she’d been up half the night crying. Could have been. She was wearing one of those silky kimono dressing gowns. Very nice. I made a mental note of it, in case it became relevant later.

"I'd like to ask you a few questions about your husband," I said.

“Now?” Incredulously.

“I’m here now, so yes. Now would be a good time.”

She shook her head, but opened the door wide so that I could enter. I followed her down a long hallway into a large, bright kitchen. All the cabinets were glossy blue, and the floor had black and white tiles. Like something you’d see in an art gallery.

"I thought the police file was closed? They said there were no suspicious circumstances, nothing to worry about there?" Mrs Odell poured herself a coffee from a percolator, then turned and looked at me. “Coffee?”

“Milk and three, thanks. No, there are just a few loose ends to tidy up. Mrs Odell, did you know your husband smoked?”

She put the coffee in front of me and sat down heavily at the kitchen table. She looked worn out. No make-up. I suddenly realised that I had never seen my mother without make-up. She had always had a perfectly painted mask. I mean face.

Ha ha.

"He smoked socially," said Mrs Odell. "Like me. We'd have the occasional cigarette with a drink. Why is this important?"

"Good question, Mrs Odell. At this stage, I'm not sure. So you knew all about his smoking? He wouldn't hide it from you?"

"Of course not." She pulled her hands through her hair, rubbed them over her face.

"The children? Would he hide it from them?"

"No, no. Quentin is eighteen, they smoke cigars together sometimes. And Poppy – well, she never liked his smoking, but she never made a big deal out of it. And Greg wasn’t a liar."

Little liar. Clean your mouth with soap.

"Mind if I take a look around?"

Mrs Odell shrugged. I bet that felt nice, shrugging in that silky kimono. "If you must."

I went into the living room. They had a piano and a chaise longue. I guessed that was all Mrs Odell's doing, the fancy interior decoration bit. Looked like something out of one of those magazines Mother used to read. Apart from that, it wasn't special. There was nothing in there that interested me. The dead man's study, though, that was more promising. He brought a lot of work home with him, by the looks of it. I had a quick rummage through his desk, saw nothing of importance. Picked up his photographs – him and his wife and kids, all smiling into the camera. Well, you would smile, wouldn't you? Living this life. Nothing, again nothing. Some instinct made me push the door to, so I could see behind it. Hanging from the back of the door was another photograph, this one black and white. There were two adults wearing formal clothes, and a child standing between them. A boy. Must have been only four or five, in his Sunday best. His father had his hand in the boy's hair.

If you don't smile for the camera I'm going to pull the hair right off your head.

I picked the photo from the door and went back to the kitchen. Mrs Odell was dressed now, in a simple jumper and jeans. How elegant she was. How poised. I put the photograph on the kitchen table.

"Who are those people?" I asked.

She picked up the photograph. A flicker of a smile crossed her face. "That's Greg, when he was a little boy. And his parents."

"They're still alive?"

"His father is," she said. "In fact, he was coming to stay with us that day, the weekend… He didn't come, though. I rang him, of course, as soon as we heard."

I could feel Poppet jumping up and down in my pocket, squirming with excitement. I knew she was right, we'd found the killer. But I didn't feel good about it. I felt like my stomach had turned into a stone.

On the Monday, Newlove told me she had put in for a new partner. She said she couldn't handle all my 'strange obsessions' and she even suggested I go and see a counsellor.

Poppet loved that. She laughed so hard she almost burst a seam.

"You think I'm crazy?" I asked Newlove.

"I don't know. I'm not a doctor, am I?" She blew a smoke ring, and we both watched it wobble upwards.

"Let me explain again," I said. "He killed himself because he couldn't face his father. His father used to beat him that hard. You can tell, from how he's standing in the photo. He was a stern, cruel man. Odell had to hide everything from him – his drinking, his smoking, everything. He couldn't take it in the end. Couldn't face the thought of seeing his own father. So he fell into the canal. Accidentally on purpose, if you know what I mean." It made sense to me. All those years, the fearful years of childhood. You can’t ever just leave them behind, not even a man like Odell, with all his money and success. He was carrying it around like bricks in his pockets – it was sure to sink him in the end.

Newlove shook her head. "Even if that were all true, which seems pretty unlikely to me, no one has committed an actual crime, have they? Except maybe you. Mrs Odell has made a formal complaint. She thinks you think you’re fucking Columbo or something. And you've just wasted all that time and energy and goodwill to try to prove something that is totally fucking irrelevant and unimportant."

Tell her about the crocodiles, Poppet whispered. Tell her what happened next, after the rice pudding. So she’ll understand.

"I'm sorry," I said. "You're right, obviously you are. This case has got to me, that's all."

"It's not a case! It's all in your damn head." Newlove stamped her cigarette out on the ground. I’d never seen her so cross.

It's all in your silly little head. You're always making things up, silly boy.

I took the rest of the day off and went home. Locked myself in the Evidence Shed and went through all of the special evidence. I took it out of the bags and lined it up on the shelf. Then I decided I needed to see it in a different context, so I brought the pile of things into the house and took it through to the front room. We hardly ever used the front room – that was for special occasions and guests. All the best furniture was in there and you had to keep it nice, everything polished, expensive air freshener too, scented candles and that. I put the evidence on the table in there. It all looked really dirty in that nice, clean room. I put the encyclopaedia on the table too, all seven volumes, stacked high.

The glittering crocodiles.

The glittering crocodiles. I found them under 'N' for the Nile. Funny how the picture had faded, in my memory. Now, on the page, they were bright and vivid as new.

What are you looking at?

Look, Mummy! Crocodiles.

Eat your pudding. Stop whining.

I brought the spoon to my mouth. I hated rice pudding. The maggotty-white rice swimming in sickly sweet curdled milk. I pretended to put the spoon in my mouth, but instead put it back into the bowl. She saw.

Upstairs. Now.

I sat in the window of my bedroom, with the encyclopaedia and the bowl of rice pudding. Not the dessert bowl, but the big glass dish she had made it in. And she sat beside me, her long legs in her high-heeled black shoes, flexing her ankles, digging the stiletto points into the carpet. She lit another cigarette, took a few puffs, and flicked the ash onto the milk skin that had formed across the top of the pudding.

Eat your rice pudding. It's your favourite.

#

It took a while before I fully understood the message I'd been given by Greg Odell. But one Sunday evening, not too long afterwards, I drank half a bottle of good single malt, and packed the special evidence into a sports bag. Slung it over my shoulder and walked to the canal, the quiet bit where Greg Odell had been dragged up. It was gloomy down there; I half expected mist to rise up from the water, like some old Sherlock Holmes movie.

I filled my pockets with stones, gravel, bits of brick left lying on the towpath. Didn’t really feel heavy enough to sink me, but the weight was starting to drag my jeans down. It got harder to move. I stuffed a load of bricks in my bag and slung it over my shoulder. That would do it.

Get on with it, then.

I took Poppet from my pocket, looked at her flat doll's face. It would be just as easy to take her down with me. What would she do without me, anyway? Or I could leave her here, at the side of the canal, hanging in the bushes. I crammed her into my pocket, head first, into the gravel.

They’re going to drag your stinking body up and it’s going to reek, and then you’ll always be remembered as that stinky stinky stupid boy.

Shut up.

No, I want you to do it. Kill yourself, go on. You’ve nothing to live for.

I stayed on the towpath for a while, thinking about it. After a while, I threw the bag in and watched it sink below the brackish water. There was an old bike abandoned in the hedge behind me, and I threw that in after it. Knew then that I wasn’t going to do myself in. I’m not the type, am I? Haven’t got the poetic bent or whatever. But it felt good to say goodbye to all that stuff. I didn't know if I should maybe say a few words, say a prayer or something. It was the last of my mother, after all. Well, not quite the last of her, perhaps. It was all just crap, really, but you know. I guess I’m sentimental. Anyway, I didn’t say anything because I would have felt like an idiot, talking to myself in the dark.

I stood for a while, looking in the canal, and it was getting dark; just the reflection of the moon let me know where the water’s edge was. Then I saw something in there. Just a flash of something. Green and white, it was. A sparkle as it dived beneath the water. Something like diamonds, glittering diamonds, pouring off its scaly back.

Oh shut up, said Poppet. Idiot child.

I crushed her head in my fist, and thought I heard a tiny yelp. "Let's just go home," I said, and we did.

The End.

You can't beat a good editor… Sadly, it's not legal to beat a bad one. Really hard to fathom how this would work without Poppet. Or even why someone would think that.

You write so good!

What a great read on a Monday morning, and I really cannot imagine this story without Poppet. Poppet is it's soul! Anyway, reading this I've got the urge to go and write now. See you!